The idea here is the following. We have a Hamiltonian $H$ that is a self-adjoint operator on the global Hilbert space $\mathcal{H}$, which can be split into a large easy part $H_0$ and a perturbation $V$. We are only interested in a small part of the spectrum (usually the ground state, or a handful of states just above it).

Further, we restrict ourselves to the case that the “easy part” of the spectrum consists solely of $H_0$ eigenstates ${\ket{m}}$. We call this the model space $\mathcal{M} = $Span${\ket{m}} \subset \mathcal{H}$. We want to develop an effective Hamiltonian $H_{eff}:\mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}$ that has the same eigenvalues as $H$ on a small subset of its eigenfunctions, or more formally, that corresponds to the linear projection of $H$ onto $\mathcal{M}$.

We define the projection operator $P : \mathcal{H} \to \mathcal{M}$ by $P = \sum_{m} \ket{m} \bra{m}$. Clearly $P^2 = P = P^\dagger$. It will be convenient to define $Q = 1-P$ for later use.

Formally, the defining property of $H_{\text{eff}}$ is that any true eigenstate $\ket{\psi}$ satisfying $H \ket{\psi} = E\ket{\psi}$ should also satisfy

\[H_{eff} P \ket{\psi} = E P \ket{\psi} \hspace{3em}[1]\]We now seek an explicit formula for $H_{eff}$ in terms of $V, H_0, \ket{n}, \epsilon_n$. The game here will to be splitting the solution $\ket{\psi}$ into two orthogonal components, in such a way that the final equation is in terms of $P\ket{\psi}$ only.

The original Schrödinger equation may be re-expressed as $(E - H_0) \ket{\psi} = V\ket{\psi}$. Since $\mathcal{M}$ is the span of $H_0$ eigenstates, it follows that $[H_0, P] = 0$. It follows that

\[(E-H_0) Q \ket{\psi} = QV \ket{\psi} \hspace{3em}[2]\]If $E-H_0$ is nondegenerate (i.e. $E$ does not overlap with an eigenvalue of $H_0$), it is clear to see that in the finite dimensional case this operator is full rank and therefore invertible. (Hint: $H = UDU^\dagger \Rightarrow (E-H_0) = U(E-D)U^\dagger$) It is clearly a map $\mathcal{H} \to \mathcal{H}$, and can be constructed explicitly as

\[K = \sum_{\alpha} \frac{\ket{\alpha} \bra{\alpha}}{E - \epsilon_\alpha} \hspace{3em}[3]\]It is simple to show that $(E-H_0)K = K(E-H_0) = 1$. Applying $K$ to [2] gives the useful relation

\[Q\ket{\psi} = KQV\ket{\psi} \hspace{3em}[4]\]The Wave Operator

It’s possible to decompose $\ket{\psi}$ in a trivial way, and recursively apply equation [4] to get a series expansion.

$ \ket{\psi} = (P + Q) \ket{\psi} = P\ket{\psi} + KQV\ket{\psi} $

$ = [1 + KQV]P\ket{\psi} + KQVQ\ket{\psi} $

Iterating the process of inserting $P+Q$’s and expanding $Q\ket{\psi}$ gives

$ = \sum_{j=0}^\infty (KQV)^j P \ket{\psi} := \Omega(E) P\ket{\psi} $

$\Omega(E)$ is sometimes called the wave operator, and it seemingly does the impossible - mapping something in $\mathcal{M}$ to a unique element of $\mathcal{H}$ as though it is $P^{-1}$. Such an object clearly does not exist, since $P$’s kernel is most of the Hilbert space.

The subterfuge here comes from convergence of the series. In the self-referential step, we implicitly assumed that $\lim_{N\ to \infty} (KQV)^N \ket{\psi} = 0$, which only holds true for certain choices of $V$ and states in a certain subspace of $\mathcal{H}$. I don’t believe it’s possible to find a more useful specification of this subspace without choosing a specific $V$. We see that there are obvious issues if $E$ is an eigenvalue of a model space element. We’ll worry about it as it emerges.

It’s also worth noting that we could have used a subtly different operator to invert $E-H_0$, \(K'(E) = \sum_{\alpha \in \mathcal{M}^\perp} \frac{\ket{\alpha}\bra{\alpha}}{E-\epsilon_\alpha}\) which has the advantage of being defined even if $E$ overlaps with an energy in $\mathcal{M}$. Kitaev calls this object $G_0’(E)$. Wherever $K$ is defined, $K’(E) = QK(E)Q = QK(E)$

The Effective Hamiltonian

Hitting the Schrödinger equation with $P$ on both sides gets you

\[(E-H_0)P\ket{\psi} = PV \ket{\psi}\]Supposing that $\ket{\psi}$ has sufficient overlap with the model space for $\Omega(E)$ to converge, we’re essentially done.

\[P V \Omega(E) P \ket{\psi} = (E-H_0) P \ket{\psi}\] \[H_{eff} P \ket{\psi} = E P \ket{\psi}\]where $H_{eff}$ has been identified with $P\left[H_0 + V\Omega(E) \right]P$.

It is usually the case that $\mathcal{M}$ is completely energy degenerate, in which case $PH_0P\equiv \epsilon_0$ is a trivial constant that can be dropped.

The series expansion of $H_{eff}$ sometimes written as

\[H_{eff} = (H_0 +) P\left[ V + V\frac{Q}{E-H_0}V + V\frac{Q}{E-H_0}V\frac{Q}{E-H_0}V + ... \right] P\](We used a hidden $P^2 = P$ for this step)

The notation $\frac{Q}{E-H_0} \equiv Q K$ is unambiguous since these operators commute.

Non-Perturbative effects

One may be led to believe that we’ve solved many body quantum mechanics with this - $\Omega$ seemingly grants you access to the whole spectrum of the Hamiltonian by studying only a very small part of its eigenspace. This is of course too good to be true. We only have access to the subspace of $\mathcal{H}$ on which $\Omega$ is convergent, the ‘perturbative subspace’ if you like. Perturbation theory will not reveal any other states, including instantons and some solitons. In general, it will not get you the correct ground state either, cf. confinement.

Finding the energy E

As written, we do not yet have a solution - the exact energy $E$ appears on both sides of the equation

\[H_{eff} P \ket{\psi} = E \ket{\psi}\]This is the so-called Brillouin-Wigner framework, which one may in principle solve self-consistently. Alternatively, it is possible to move to the Rayleigh-Schrödinger framework that, rather than relying on the existence of an operator inverse, computes the series expansion of $\Omega$ recursively (and without knowing $E$).

First, we write $\Omega = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \Omega_n$, where $\Omega_n$ is of order $n$ in $V$ and $\Omega_0 = 1$. (The argument from earlier shows that $\Omega_n = (KQV)^n$, but what follows does not need us to know $K(E)$ explicitly).

Theorem: When the domain is restricted to $\mathcal{M}$, it is the case that

\[[ \Omega_n, H_0 ] = QV \Omega_{n-1} - \sum_{j=1}^{n-1}\Omega_j P V \Omega_{n-j-1}\]Proof:

Start with the equation $V \ket{\psi} = (E - H_0) \ket{\psi}$. We use the fact that for any (perturbative) $\psi$, $\Omega P \ket{\psi} = \ket{\psi}$, i.e. $\Omega P$ is a projection operator that is unity in the relevant subspace.

\[\left[\Omega H_0 P - H_0 \Omega P \right] \ket{\psi} \\ = \left[ (E - \Omega P V \Omega P) - (E - V\Omega P ) \right] \ket{\psi}\]From this it is clear that when acting on model-space states $\mathcal{M}$, \([\Omega, H_0] = (1-\Omega P)V\Omega.\) Expanding $\Omega$ and comparing powers of $V$ yields

\[[\Omega_n, H_0] = V\Omega_{n-1} - \sum_{u+v + 1 = n} \Omega_u PV\Omega_v\\ = V\Omega_{n-1} - \sum_{u=0}^{n-1} \Omega_u PV\Omega_{n-u-1}\]Which (modulo some index shuffling) is the result that we wished to prove.

Finally, note that the expansion for the effective Hamiltonian $H_{\text{eff}} : \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}$ is $H_{eff} = P H_0 P + P H_1 P + P H_2 P + … $, where $H_n = V \Omega_{n-1} \forall n \in \mathbb{Z}_{> 1}$, and $H_0$ is the unperturbed Hamiltonian from before. If we can determine the values of $\Omega_n$, then we have an $n$th order approximation to the effective Hamiltonian.

Taking matrix elements

Adopt the notation $\ket{a}, \ket{b}, … \in \mathcal{M}$, $\ket{x}, \ket{y}, … \in \mathcal{H}$.

The projectors mean that the only relevant matrix elements are $\bra{a} H_n \ket{b}$. What follows must be done iteratively -

$\bra{a} H_0 \ket{b} = \epsilon_a \delta_{ab} $

$\bra{a} H_1 \ket{b} = \bra{a}V\ket{b} $

$\bra{a} H_2 \ket{b} = \sum_x \bra{a} V \ket{x}\bra{x}\Omega_1 \ket{b}$

We need to infer $\Omega_1$ from the commutator relation above:

$\hspace{2em} \bra{x} [\Omega_1, H_0] \ket{b} = \bra{x} QV \ket{b}$

$\hspace{2em} \Rightarrow (\epsilon_b - \epsilon_x) \bra{x} \Omega_1 \ket{b} = \bra{x} QV \ket{b}$

As written, we know that if $x \in \mathcal{M}^\perp, b\in \mathcal{M}$, then $\epsilon_b - \epsilon_x \neq 0$ and we can invert the left hand side:

\[\bra{x} \Omega_1 \ket{b} = \frac{1}{\epsilon_b - \epsilon_x}\bra{x} QV \ket{b}\]This works, but leaves $\Omega_1$ unprescribed if $\ket{x} \in \mathcal{M}$. However, from the ‘implicit’ definition above $ \Omega_n(E) = \left[Q(E-H_0)^{-1}V\right]^n $, we see that all $\Omega_n$ have a range that is strictly $\mathcal{M}^\perp$, i.e. $\Omega_n \equiv Q \Omega_n$ for $n\ge 1$.

Finally, we have the result

\[\bra{a}H_2 \ket{b} = \bra{a} V \sum_{x \in \mathcal{M}^\perp }\ket{x}\bra{x} \frac{1}{\epsilon_b - \epsilon_x} QV \ket{b}\\ = \bra{a} V \sum_{x \in \mathcal{M}^\perp }\ket{x}\bra{x} \frac{1}{\epsilon_b - H_0} QV \ket{b} = \bra{a} V \frac{1}{\epsilon_b - H_0} QV \ket{b}\]A similar calculation for $H_3$ yields one term beyond the neatural generalisation of the series,

\[\bra{a} H_3 \ket{b} = \bra{a} V \frac{1}{\epsilon_b - H_0} Q V \frac{1}{\epsilon_b - H_0} Q V \ket{b} - \sum_c \bra{a} V \frac{1}{\epsilon_b - H_0} \frac{1}{\epsilon_c - H_0} Q V \ket{c} \bra{c} V \ket{b}\]Examples and Applications

Ordinary degenerate perturbation theory

We derive here an important special case, where every state in the model space $\mathcal{M}$ has the same unperturbed energy.

Field theory and the self energy: why $K$ is a Green’s function

Supposing that $H$ is a differential operator (i.e. an operator on an infinite dimensional space rather than a finite dimensional one), a familiar concept from PDE theory is the Green’s function

\[G(x,t | x',t')\]defined to be the integral kernel required to invert a linear differential operator $\mathcal{L}$, i.e.

\[\mathcal{L} \psi(x, t) = \rho(x,t) \Leftrightarrow \psi(x,t) = \int d^dx' dt'\, G(x,t | x', t')\rho(x',t')\]Some technicalities that are often brushed over:

- By $\mathcal{L}$, I mean some kind of sum of functions and derivatives and the boundary conditions that $\psi$ satisfies.

- Green functions are in general different to the propagator, which is the fundamental solution of the PDE. Propagators are independent of boundary conditions.

- A “Green function” in mathematics means any function that inverts the linear differential operator. This is unique for a Laplace-like linear operator with boundary conditions (because any harmonic function vanishing on the boundary is identically zero), but is not unique for the wave equation. However, in physics there is generally a canonical choice of Green’s function for the situation - see the discussion here

- Various physical quantities in physics are Green functions, though with subtle differences that can bite you. See here for a valiant attempt at disentangling these notions.

Fix some $E$, and further, assume that $E$ is such that $E-\hat{H}_0$ and $E-\hat{H}$ are invertible.

Then we define

\[\hat{G}_0 \equiv [E-H_0]^{-1} \hspace{2em} \hat{G} \equiv [E-H]^{-1}\]In the many-body context, the standard setup is that $H_0$ is the noninteracting/free theory - only $H$ captures the interactions. $H_0$ is block diagonal with respect to the many body Hilbert space, $H$ is not.

One can usually write down $G_0$ with very little work - in the nonrelativistic case, a single free particle has

\[\hat{G}_0^{(1)}(E) = \int d^dk \frac{1}{E-k^2/2m} \ket{k}\bra{k}\]In the many body Hilbert space, this needsto be promoted to a sum over all $N$ subspaces - i.e. $G_0 = \sum_{j=0}^{N-1} 1^{\otimes j} G_0^{(1)} 1^{\otimes N-j-1}$. Physicists do not generally bother with such nuances, and quote expressions for $\hat{G}_0^{(1)}(E)$ as the definition of $\hat{G}(E)$, but in the context of this page’s story it’s an important distinction.

We wish to compute (some approximation to) the influence of the many-body Hamiltonian on the single-particle space. But we’ve already solved this problem - we know how to contruct $H_{eff}$ acting only on the single-body space, and then we can simply define

\[G_{eff} \equiv PGP = [E-H_{eff}]^{-1}\] \[= \left[E - H_0 - PV\sum_{n=0}^\infty \left(\frac{QV}{E-H_0}\right)^n P \right]^{-1}\] \[= \left[E - H_0 - PV\left(1-\frac{QV}{E-H_0}\right)^{-1} P \right]^{-1}\]The discussion so far is valid for a very general class of operators.

Now we specialise to particles represented by the uncountable momentum basis moving under a Hamiltonian with time- and position- translation symmetry. We also ignore the subtlety that the momentum space representation of the Hamiltonian may in general contain $k$ derivatives, since this does not happen very often in “garden variety” solutions.

It can be shown (exercise) that the “effective Green’s function” has the famous representation

\[G(k, \omega| k', \omega') \equiv \frac{1}{E-(\omega - \omega') - \Sigma(k-k' ,\omega-\omega')}\]where $\Sigma$ is the self energy that exactly accounts for the influence of all orders of perturbative corrections.

Examples

Quantum spin ice

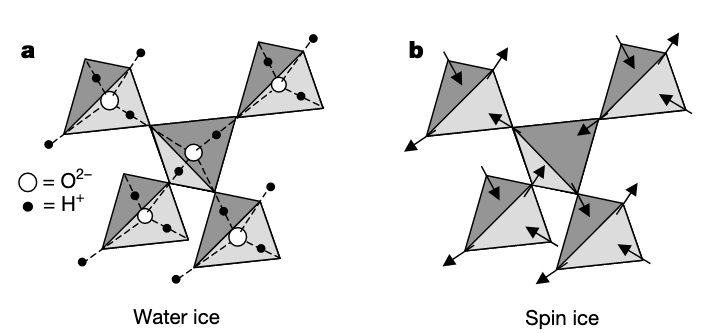

Consider the pyrochlore lattice. By playing around with the 3D model, you should be able to convince yourself that the pyrochlore sites live on the bonds of a diamond lattice. Imagine that we want to simulate something approximating water ice, in the diamond-crystal phase. In that case, we might be tempted to place an oxygen atom at each diamond site and associate the hydrogen bonds with pyrochlore sites. There is an extensively degenerate number of ways to do this, i.e., to assign to each pyrochlore site an “in” or “out” alignment. The diamond lattice is bipartite, so one may choose one FCC sublattice to be the reference point and define in and out by whether the spin points towards the reference point.

We can promote the notion of “in/out” to an Ising degree of freedom, and in so doing obtain spin ice.

Stolen from this 2001 (open access) paper

Stolen from this 2001 (open access) paper

The Hamiltonian giving rise to this highly frustrated ground state is \(H_0 = J_{zz}\sum_{\langle ij \rangle} S^z_i S^z_j\), $J_{zz}>0$. This is the Anderson ice model.

This is an Ising model, so does not possess any quantum fluctuations. It is customary to also consider an XXZ type perturbative hopping,

\[V = \frac{J_\perp}{2} \sum_{\langle ij \rangle} S^+_i S^-_j + S^-_iS^+_j\]The perturbation can be thought of as a hard-core boson hopping on this lattice. A chain of three tetrahedra can be represented as follows -

The rule is that any non-vanishing correction can’t change the ‘charge’ on any tetrahedra. It is clear that the perturbation vanishes at first order - there’s no way to restore charge to the two edge spheres. Likewise, the only nonvanishing second order contribution corresponds to swapping two spins then swapping them back, which is a constant energy shift.

The leading order dynamical contribution comes at third order, from the ‘ring flip’ term that acts on hexagons like the one below (B tetrahedra are drawn larger, with dotted lines):

Exercise: Figure out what the constant term is to third order.

For a detailed breakdown of the constant terms, see the paper by Hermele, Fischer and Balents

The effective Hamiltonian is

\[H_{eff} = -\frac{3J_\perp^3}{2J_{zz}^2} \sum_{p} \mathcal{O}_p + \mathcal{O}_p^\dagger + constant\]The $3/2$ comes from the fact that each plaquette has six possible counterclockwise hoppings (and another six clockwise, captured by the $\mathcal{O}^\dagger$), while the energy of the intermediate excited state is $2J_{zz}$, giving an overall contribution of $\frac{6J_\perp^3}{(2J_{zz})^2}$.

This is far from the end of the story, but that is a tale for another post.

The dimerised limit of the Kitaev model

Suppose we have a Kitaev model with $|J_z| \gg |J_y| + |J_z|$. See page 19 of Kitaev’s paper for details on what this means.

Then the natural choice of base Hamiltonian is

\[H_0 = - J_z \sum_{\langle ij \rangle^z} \sigma^z_i \sigma^z_j\]with perturbation

\[V = - J_x \sum_{\langle ij \rangle^x} \sigma^x_i \sigma^x_j - J_y \sum_{\langle ij \rangle^x} \sigma^y_i \sigma^y_j\]The ground state is massively degenerate, consisting of $N/2$ decoupled dimers with doublet ground states - in the ferromagnetic $J_z>0$ case, these are $\ket{\uparrow\uparrow}$ and $ \ket{\downarrow \downarrow}$ in the $\sigma^z$ basis. These doublets, represented by thick lines below, are then coupled nontrivially by the weak bonds. Set the ground state energy $E_0 = 0$.

If we flip, say, an $x$ bond between the dimers $r$ and $s$ we leave the ground state manifold - writing $r_1 (r_2)$ for the upper (lower) spin in the singlet acting $V$ on any ground state gives you

\[-J_x\sigma^x_{r_1}\sigma^x_{s_2} \ket{\uparrow \uparrow}_r \ket{\downarrow \downarrow}_s = = \ket{\downarrow \uparrow}_r \ket{\downarrow \uparrow}_s\]This gets projected to zero by $P$.

The game to play is to keep adding powers of $V$ until you get something nonzero/nonconstant.

In order to get something nonzero, we have to either flip one of the spins twice (giving you the same state you started with) or flip both spins in the dimer. At second order, we can get something nonzero with processes that apply the same link twice -

\[J_x^2 \sigma_r^x \sigma_s^x \frac{Q}{E-H_0}\sigma_r^x \sigma_s^x\] \[= \frac{J_x^2} {E-J_z} 1\]and likewise for the $y$ bonds. These do not move you in $M$ - they are scalar multiples of the identity in the model space. Such terms are usually dropped as constant energy shifts.

Since we are in the strongly gapped regime, it’s completely legitimate to expand $E to zeroth order in the perturbation and replace it by $E_0 = 0$. In general, this will give corrections to the coupling constants when higher order terms are taken.

Exercise: Show that for this model, all odd-powered terms vanish.

The leading non-constant term is at fourth order, consisting of plaquette operators proportional to

\[Q_p = \sigma^x_{1'}\sigma^x_2 \sigma^y_2\sigma^y_{3'} \sigma^x_3\sigma^x_{4'} \sigma^y_{4'} \sigma^y_1\] \[= -\sigma^x_{1'} \sigma^z_2 \sigma^y_{3'} \sigma^x_3 \sigma^z_{4'} \sigma^y_{1}\]where primed numbers indicate coupling to the top degree of freedom, unprimed to the bottom.

(I chose the sum to go counterclockwise around a plaquette, but it’s clear from the second expression that any consistent choice gives the same answer)

The constant of proportioanlity comes from a sum over the 4! different ways of arranging these four operators, i.e. the 4! different ways of assigning terms to the $V$ placeholders in the expression $- PV\frac{Q}{H_0}V\frac{Q}{H_0}V\frac{Q}{H_0}VP$. Regardless of whether the perturbations commute with each other, they certainly do not commute with $H_0$ if they are not trivial - all 24 terms must be summed, with the energies of the intermediate virtual states properly accounted for.

It can be shown (Exercise) that this procedure results in a fourth order effective Hamiltonian equal to

\[H_{eff} = -\frac{J_x^2J_y^2}{16|J_z|^3} \sum_p Q_p + constant\]where the sum runs over all hexagonal plaquettes.

Further, it can also be seen that $Q_p$ is nothing more than the projected form of the original hexagonal plaquette operator, $Q_p = PW_pP$, exploiting the fact $\sigma^z\sigma^z$ on the $z$ links always give +1.

$Q_p$ can be written in a from that makes the fact that it acts entirely within $\mathcal{M}$ obvious. It’s conventient to associate the two dimer ground states with ‘up’ and ‘down’. This allows rewriting the Hamiltonian in terms of Pauli matrices, which I’ll denote with $\tau^{x,y,z}$, understood as acting on the basis ${\ket{\Uparrow},\ket{\Downarrow}} = {\ket{\uparrow \uparrow}, \ket{\downarrow\downarrow}}$.

In particular, by noting that both of the original spins pointed in the same direction we can replace

\[\sigma_2^z \mapsto \tau_2^z\] \[\sigma_{4'}^z \mapsto \tau_4^z\]With slightly more work (e.g. by taking matrix elements), one can happily convince themselves that

\[\sigma^x_{1'}\sigma^y_1 \mapsto \tau_1^y\] \[\sigma^y_{3} \sigma^x_{3'} \mapsto \tau_3^y\]leading to the friendlier expression

\[Q_p = \tau_1^y\tau_3^y \tau_2^z \tau_4^z\](up to a possible sign error)

References

Yoshio Kuramoto, Perturbation Theory and Effective Hamiltonian