If you’re following along the Kitaev paper, you will eventually strike (on page 17) the rather crypic remark that

This statement follows from a beautiful theorem proved by Lieb [50].

I followed up on that, leading me to Lieb’s 1994 (!) paper, which incredibly can be found on arXiv. The proof was later streamlined and generalised by Macris and Nachtergaele a few years later, and it’s their proof that I’m going off here (for the most part).

There is still absolutely no way to top Lieb’s original graphic design sense though, so I’ll shamelessly

reuse his title art:

Definitions

We consider the model of spinless fermions hopping around on a lattice \(\Lambda\). (Spin will be added later.)

\[H = \sum_{x,y \in \Lambda} t_{xy}e^{i\phi_{xy}} c_x^\dagger c_y\]The \(t, \phi\) satisfy hermiticity relationships \(t_{xy} = t_{xy}, \phi_{xy} = - \phi_{yx}\). It will be convenient to refer to the \(\Lambda\) and \((t,\phi)\) interchangeably as the model, standing in for the equivalent model interpretations as a directed complex valued graph or a hermitian matrix. Physically, \(\phi\) is a U(1) gauge field / gauge connection. You can view them either as a set of numbers over which to optimise, or as the eigenvalues of some continuous U(1)-valued operator. In the second interpretation, we find the gauge sector that minimises the Hamiltonian’s energy.

Definition 1: Let \(\gamma\) be an oriented closed loop in \(\Lambda\). The flux of \(\gamma\) is defined as

\[\Phi[\gamma] = \sum_{\langle xy\rangle \in \gamma} \phi_{xy}\]We also introduce a small (trivial) lemma:

fluxes are gauge invariant Define a ‘discrete scalar field’ \(\theta:\Lambda \to \mathbb{R}\). Modulating all \(\phi_{xy} \mapsto \phi_{xy} + \theta_x - \theta_y\) does not alter the value of any fluxes. (This can be interpreted as a discretised version of \(\nabla \times \nabla f = 0\), or \(d^2= 0\) if you’re fancy)

Definition 2: A site avoiding mirror plane \(P\) is a symmetry of \(\Lambda\),

\[P : \Lambda \to \Lambda\]such that \(P(x) \neq x\) and \(t_{x,y}= t_{Px, Py}\).

If the graph is embedded into \(\mathbb{R}^D\), then this can be thought of as a mirror plane that cuts bonds but does not slice through any sites.

An interesting fact about the fluxes

This deserves its own section because of its importance in the Kitaev model.

We can define $\Phi[\gamma]$ more generally as a string operator

\[\Phi[\gamma] = \prod_{\langle ij\rangle \in \gamma} t_{ij}e^{i\phi_{ij}}c^\dagger_i c_j\]Exercise: Show that $[c^{\dagger}_jc_j, \Phi[\gamma]]$ is only nonzero when $j$ is at the

beginning or end of the chain.

Convince yourself that this proves that the loops have simultaneous eigenstates with the Fermion basis, and that $\Phi[\gamma]$ represents a fermion transport operator.

Statement of the Theorem

Let the \(t_ij\) be structured such that

- (A1) \(\Lambda\) is bipartite \(\Leftrightarrow\) all circuits on the graph have even length

- (A2) Each closed loop \(\gamma\) defined on the links of \(\Lambda\) possesses a site avoiding mirror plane.

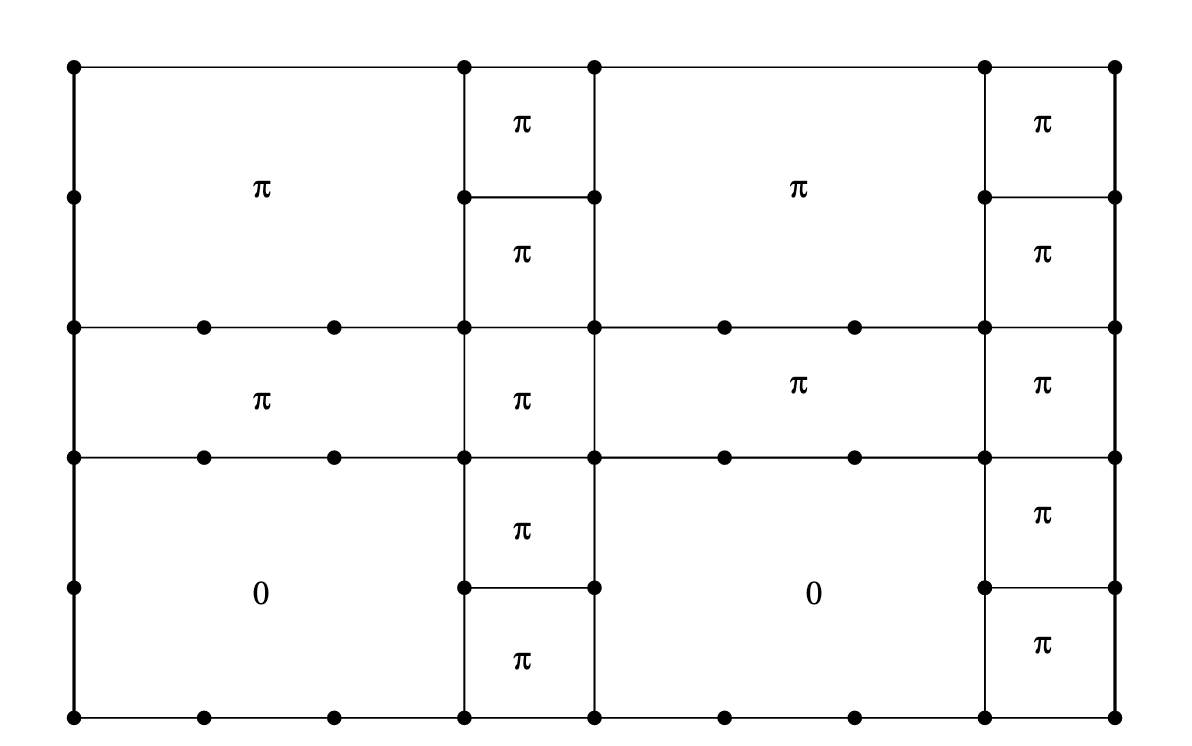

A graph satisfying A2 is shown below (taken from Macris and Nachtergaele 1996)

If (A1) and (A2) are satisfied, then the free energy \(F = -k \ln \text{tr} e^{-\beta H}\) is minimised when the fluxes are

\[\Phi(\gamma) = \begin{cases} \pi & \|\gamma\| = 0\ \text{mod}\ 4\\ 0 & \| \gamma \| = 2\ \text{mod}\ 4 \end{cases}\]where \(\|\gamma\|\) is the length of the path.

Some references only explicitly deal with the \(T=0^+\) (i.e. \(\beta=1/T \to \infty\)) limit, where the free energy is replaced by the ground state energy:

\(F = -T \ln(\text{tr} \exp(-\beta H)) = - T \ln(\sum_i e^{-\beta E_i}) \sim -T (-\beta E_0) = E_0\) where $E_0$ is the ground state energy.

Preliminaries

Complex conjugation and antiunitary operators

Complex conjugation (aka time reversal $T$) needs to be handled carefully because it is antilinear, $T \alpha = \bar{\alpha} T \forall \alpha \in \mathbb{C}$.

Its defining property is that, given a time reversible Hamiltonian $H$ with time dependent solution $\ket{\Psi(t)}$ the time reversed statevector $T\ket{\Psi(t)}$ satisfies the time-reversed Schrödinger equation,

\[i\hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial(-t)} T \ket{\Psi(t)} = H T \ket{\Psi(t)}\]We only assumed $T$ to be an operator on the Hilbert space - we have no idea if it is linear or not.

In fact, it isn’t \(\mathbb{C}\)-linear. Rearranging shows that $T^{-1} (-i) T = i$. We can require $T$ to preserve norms, which implies $\braket{T\psi \vert T\psi} = \braket{\psi \vert \psi}$ for all basis elements. It can be shown from the fact that $[T,H]=0$ and the definition that $T$ is $\mathbb{R}$-linear.

This implies that $T$ is antiunitary: an $\mathbb{R}$-linear operator where \(\braket{T\psi \vert T\phi} = \overline{\braket{\psi \vert \phi}}\). $\mathbb{R}$-linearity implies that $T(\alpha\ket{\psi} + \beta\ket{\phi}) = \overline{\alpha} \ket{\psi} + \overline{\beta} \ket{\phi}$.

Lemma There exists an orthogonal real basis of the Hilbert space that is $T$ invariant and unique up to factors of -1.

Proof: Start with any old orthogonal basis ${\ket{n}}$. I define $K$ to be the unique antihermitian operator satisfying $K\ket{n} = \ket{n}$. Viewing the Hilbert space as an $\mathbb{R}$-vector space of twice the dimension, we construct a new (doubled) basis ${\ket{n}, i\ket{n}}$. $K$ is then constructed explcitly via $K\ket{n} = \ket{n}, Ki\ket{n} = -i\ket{n}$. It follows immediately that $K$ is antilinear and $K^2 = 1$. Note that $K^\dagger$ is not defined for antilinear operators.

$KT$ and $TK$ are unitary, since $\braket{TK\phi \vert TK \psi} = \overline{\braket{K \phi \vert K \psi}} = \braket{\phi \vert \psi}$, which proves the lemma since $T KK = T = UK$ for some unitary operator $U$. Then, letting $\ket{m} = U \ket{n}$, $T\ket{m} = T TK\ket{n} = \ket{n}$. In fact, we’re being unnecessarily abstract: $U$ is diagonal (in the $\mathbb{C}$ basis), i.e. it’s a trivial phase rotation of the original basis.

Corrolary A particular basis ${ \ket{e_i} }$ has a unique associated antilinear operator $K$ that leaves every basis vector invariant.

Lemma Given a $\mathbb{C}$ linear operator $A$ on the Hilbert space $\text{Span}{ \ket{e_i} }$ with associated antilinear $K$, $\bra{e_i} KAK \ket{e_j} = \overline{\bra{e_i}A\ket{e_j}}$

Proof: \(\bra{e_i} KAK \ket{e_j} = \bra{e_i} KA \ket{e_j} = \braket{e_i, KAe_j} = \overline{\braket{Ke_i, Ae_j}} = \overline{\braket{e_i, Ae_j}} = \overline{\bra{e_i}A\ket{e_j}}\)

Corrolary In any basis, $\bra{K\phi}KAK\ket{K\psi} = \overline{\bra{\phi}A \ket{\psi}} $

This really shows up the complacency that Dirac notation breeds - it’s tempting to just absorb the K into the left hand bra, but this is only correct for $\mathbb{C}$-linear operators!

There’s not much elegance in the proof. Most of the work is actually in proving an annoying technical result.

The Annoying Technical Result (ATR)

Let \(A,B,C_j, j=1...M\) be linear operators on a Hilbert space \(\mathcal{H}\), where $A,B$ are self adjoint and there is a basis for \(\mathcal{H}\), \(( \ket{e_\alpha} )_{\alpha=1}^N\) (where $N$ may be countably infinite) such that the matrix elements $\bra{e_\alpha}C_j\ket{e_\beta}$ are real for all $j$. Call this basis the ‘real basis’ of Beverly Hills.

Define:

- The complex conjugation operator $K$ to be the unique antiunitary operator that leaves this basis invariant.

- \(H[A,B]: \mathcal{H}^{\otimes 2} \to \mathcal{H}^{\otimes 2}\) using \(H[A,B] = A\otimes 1 + 1 \otimes B - \sum_j C_j \otimes C_j\).

- $E_n(M)$ to be the $n$th eigenvalue of a hermitian matrix, ordered smallest to largest.

- Free energy of a Hamiltonian to be \(F(H) = - T \ln(\text{tr} e^{-\beta H}) = -T \ln\lefta( \sum_n e^{-\beta E_n(H)} \right)\)

The theorem then states that

- Zero temperature The lowest eigenvalue of this operator, \(E_0 \circ H[A,B] \ge \text{min} \{ E_0 \circ H[A,\overline{A}], E_0\circ H[\overline{B}, B]\}\).

- Finite temperature The free energy of this Hamiltonian does the same thing, \(F \circ H[A,B] \ge \text{min} \{ F \circ H[A,\overline{A}], F\circ H[\overline{B}, B]\}\).

$\overline{A}$ is defined by $K A K$, corresponding to the complex conjugate in its matrix representation with respect to the real basis. We’ll write $E_n(A,B)$ as shorthand for $E_n \circ T[A,B]$, and use the same shorthand for the free energy.

Let $\ket{\Omega_n}$ be the $n$th eigenstate of $H[A,B]$. With respect to the real basis, it may be expressed as $\ket{\Omega} = \sum_{ij} M_{ij} \ket{e_i} \otimes \ket{e_j}$.

We compute the Schmidt decomposition of $\Omega_n$ by taking the SVD of $M$: $M_{ij} = \sum_\alpha U_{i\alpha} \lambda_\alpha V_{\alpha j}^\dagger$ for unitary $U,V$, $\lambda_\alpha\ge 0$. This invites the definition of alternative bases for the ‘first’ and ‘second’ subspaces, \(\{ \ket{\phi_\alpha} = U_{i\alpha} \ket{e_i} \}\) and \(\{ \ket{\psi_\beta} = V_{\beta j}^\dagger \ket{e_j} \}\).

\[\ket{\Omega_n} = \sum_\alpha \lambda_\alpha \ket{\phi_\alpha} \otimes \ket{\psi_\alpha}\]Now note that $\lambda_n(A,B) = \bra{\Omega_n} H[A,B] \ket{\Omega_n}$

\[= \sum_{\alpha} \lambda_\alpha^2 \left[ \bra{\phi_\alpha} A \ket{\phi_\alpha} + \bra{\psi_\alpha} B \ket{\psi_\alpha} \right] - \sum_{j \alpha \beta} \lambda_\alpha \lambda_\beta \bra{\phi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\phi_\beta} \bra{\psi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\psi_\beta}\]Zero temperature case

Let’s start with the case $n=0$.

Define the (normalised) ground state Ansätze

\[\ket{A} = \sum_\alpha \lambda_\alpha \ket{\phi_\alpha} \otimes K\ket{\phi_\alpha}, \hspace{2em} \ket{B} = \sum_\alpha \lambda_\alpha K\ket{\psi_\alpha} \otimes \ket{\psi_\alpha}\]Our strategy will be to show that

\[E_0(A,B) \ge \frac{1}{2} \left[\bra{A}H[A, \overline{A}] \ket{A} + \bra{B}H[\bar{B},B]\ket{B}\right] \ge \frac{1}{2}[E_0(A,\bar{A}) + E_0(\bar{B}, B)]\]The second inequality follows from the variational principle. The first requires us to expand the expression

\[\frac{1}{2}\left[\bra{A} H[A,\bar{A}] \ket{A} + \bra{B} H[\overline{B}, B] \ket{B} \right]\] \[= \frac{1}{2}\sum_{\alpha} \lambda_\alpha^2 \left[ \bra{\phi_\alpha} A \ket{\phi_\alpha} + \bra{K\phi_\alpha} KAK \ket{K\phi_\alpha} + \bra{K\psi_\alpha} KBK \ket{K\psi_\alpha} + \bra{\psi_\alpha} B \ket{\psi_\alpha}\right] - \frac{1}{2}\sum_{j \alpha \beta} \lambda_\alpha \lambda_\beta \left[ \bra{\phi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\phi_\beta} \bra{K\phi_\alpha} C_j \ket{K\phi_\beta} + \bra{K\psi_\alpha} C_j \ket{K\psi_\beta} \bra{\psi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\psi_\beta} \right]\]Now, use Hermiticity of $A,B$ to get $\bra{K\phi}KAK\ket{K\phi} = \overline{\bra{\phi}A \ket{\phi}} = \bra{\phi}A\ket{\phi}$ and reality of $C$ to get $\bra{K\phi_\alpha} C_j \ket{K\phi_\beta} = \bra{\phi_\beta} C_j \ket{\phi_\alpha}$, $\bra{K\psi_\alpha} C_j \ket{K\psi_\beta} = \bra{\psi_\beta}C_j\ket{\psi_\alpha}$

\[= \sum_{\alpha} \lambda_\alpha^2 \left[ \bra{\phi_\alpha} A \ket{\phi_\alpha} + \bra{\psi_\alpha} B \ket{\psi_\alpha}\right] - \frac{1}{2}\sum_{j \alpha \beta} \lambda_\alpha \lambda_\beta \left[ \bra{\phi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\phi_\beta} \overline{\bra{\phi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\phi_\beta}} + \overline{\bra{\psi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\psi_\beta}} \bra{\psi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\psi_\beta} \right]\]Now, letting $u = \bra{\phi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\phi_\beta}, v = \bra{\psi_\alpha} C_j \ket{\psi_\beta}$, the situation we have is

\[E_0(A,B) - \frac{1}{2} \left[\bra{A}H[A, \overline{A}] \ket{A} + \bra{B}H[\bar{B}, B]\ket{B}\right]\] \[= \sum_{j} \sum_{\alpha \beta} \frac{\lambda_\alpha \lambda_\beta}{2} \left[ |u|^2 + |v|^2 - 2|uv| \right] \ge 0\]using the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality and appropriate symmetries. This proves the result we needed for the case $n=0$, i.e. the zero temperature limit.

It then follows straightforwardly that the energy can always be decreased by letting $B = \bar{A}$, so this configuration is (at least one) ground state.

\[\square\]Finite temperature

Exercise: show that the finite temperature case of the theorem is equivalent to showing that

\[\sum_n e^{-\beta E_n(A,B)} \le \text{min} \left\{ \sum_n e^{-\beta E_n(A,\overline{A})}, \sum_n e^{-\beta E_n(\overline{B}, B)} \right\}\]When we take $\ket{A_n}$ constructed as before (from the Schmidt decomposed $\ket{\Omega_n}$), $E_n$), we can play a similar game to what we did earlier.

We already know that

\[E_n (A,B) \ge \frac{1}{2} \left[\bra{A_n} H[A,\overline{A}] \ket{A_n}+ \bra{B_n} H[\overline{B},B] \ket{B_n} \right]\]Some light algebra gets you as far as the left hand equality:

\[\sum_n e^{-\beta E_n(A,B)} \le \frac{1}{2} \left[ \sum_n e^{-\beta \bra{A_n} H[A,\overline{A}]\ket{A_n} }+ \sum_n e^{-\beta \bra{B_n} H[\overline{B}, B] \ket{B_n}} \right]\]All that remians to do is show a finite temperature version of the variational principle, which is a bit subtle to show but ultimately true.

Claim: Suppose $\ket{\psi_n}$ is an orthonormal basis for the Hilbert space. Then

\[\sum_n \exp(- \beta \bra{\psi_n} \hat{H} \ket{\psi_n}) \le \text{tr}\left(\exp(-\beta \hat{H})\right)\]The intuition to have here is that the ground state ‘estimate’ $\ket{\psi_0}$ is definitely not better than the true ground state, and even is $\psi_1$ gets more of the true ground state, it matters less because of the exponential.

I think the way to do this is to make a continuity argument based on $\beta$: We know it’s true when $\beta \to \infty$, and it’s easy to see that as $\beta \to 0^+$ you asymptotically have

\[\sum_n 1 - \bra{\psi_n} H \ket{\psi_n} \le 1 - \text{tr}(H) \le \psi_n 1\]which is hard to argue against, since $\psi_n$ is an orthonormal basis. If you take into account that

\[\langle E \rangle_{\psi_n} \ge \langle E \rangle \Rightarrow \frac{\partial}{\partial \beta}\left[ Z[\beta] - \tilde{Z}[\beta] \right]\]you have the result proven via Rolle’s theorem.

Proving the flux phase theorem

There are three steps involved in transforming $H$ into the form of the annoying technical result (ATR).

- Jordan-Wigner like transformation

- Gauge transformation

- Particle/hole symmetry

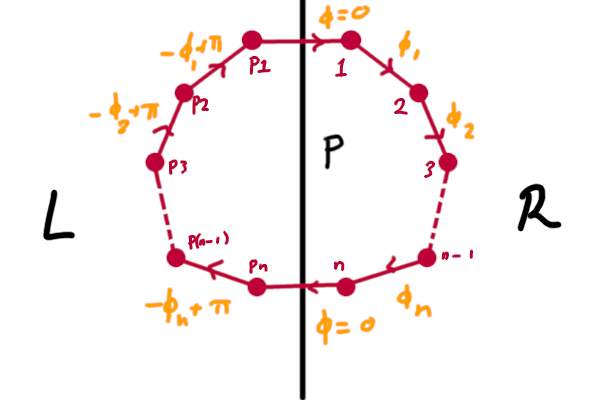

Consider a loop $\gamma$, with associated site avoiding mirror plane $P$. By assumption, $P$ divides the lattice $\lambda$ into two groups with a one to one correspondence between them, which we’ll call $\Lambda_L,\Lambda_R$ for the ‘left’ and ‘right’ sites.

The JW like transform is

\[d_x = (-)^{N_L}c_x, d_x^\dagger = c_x^\dagger (-)^{N_L}\]where $N_L = \sum_{x\in L} c_x^\dagger c_x$ is the number of fermions on the left.

Exercise: the $d$’s are still fermions.

The (original) Hamiltonian gets a minus sign on all terms that involve left-right exchange.

\[H = \sum_{x,y \in \Lambda_L} t_{xy} e^{i\phi_{xy}} d_x^\dagger d_y + \sum_{x,y \in \Lambda_R} t_{xy} e^{i\phi_{xy}} d_x^\dagger d_y - \sum_{x\in \Lambda_L, y \in \Lambda_R} t_{xy} e^{i\phi_{xy}} d_x^\dagger d_y -\sum_{x\in \Lambda_L, y \in \Lambda_R} t_{xy} e^{-i\phi_{xy}} d_y^\dagger d_x\]We established earlier that the gauge fluxes are invariant under a local U(1) rotation $d_x \to e^{i\theta_x} d_x$. (It’s clear that this transformation alters neither eigenstate nor spectrum) The even-memberedness of the loop guarantees that there exist some gauge transform $\phi \mapsto \phi’$ such that $\phi’ = 0$ on all links between $L$ and $R$.

Now use the antiunitary particle-hole symmetry $d\leftrightarrow d^\dagger$ (corresponding to a swap $\ket{0} \leftrightarrow \ket{1}$ in the Hilbert space), applied to the right sites only, to get

\[H = \sum_{x,y \in \Lambda_L} t_{xy} e^{i\phi_{xy}} d_x^\dagger d_y + \sum_{x,y \in \Lambda_R} -t_{xy} e^{-i\phi_{xy}} d_x^\dagger d_y + \sum_{x\in \Lambda_L, y \in \Lambda_R} -t_{xy} d_x^\dagger d_y^\dagger + \sum_{x\in \Lambda_R, y \in \Lambda_L} -t_{xy} d_x d_y\]It can readily be shown that the $L$, $R$ and $LR$ terms satisfy all of the necessary constraints to be regarded as the $A,B, \sum_jC_j\otimes C_j$ from the ATR when acting on the split Hilbert space $\mathcal{F}_L\oplus\mathcal{F}_R$.

If follows that the free energy $F$ is minimised when $A = \bar{B}$, i.e. $e^{i\phi_{Pi,Pj}} = -e^{-i\phi_{i,j}} \Leftrightarrow \phi_{Pi,Pj} \equiv -\phi_{i,j} + \pi\ \text{mod}\ 2\pi$.

In terms of the original (i.e. physical) basis $c_j$, this translates to requiring $\phi_{ij} = \phi_{Pi,Pj} + \pi\ (mod\ 2\pi)$.

Now consider the flux of the loop $\gamma$. For the gory details written out with indices see the paper, but I find the sketch more convincing:

To see the cancellation, all we need to notice it that $\Phi$ consists of $n-1$ products of $e^{i\phi_{12}} e^{i\phi_{P2P1}} = -1$.

It’s immediate from this that $\Phi(\gamma) = (n - 1)\pi\ (\text{mod}\ 2\pi) $, which is exactly the result we set out to prove. $\square$

For Majorana Fermions (Is this right??)

In fact, I think things are a lot simpler with Majoranas. Let the $c_j$ be Majoran fermions, and then get the deceptively innocent looking Hamiltonian

\[H = \sum_{ij} i t_{ij} e^{i\phi_{ij}} c_i c_j\]The $t_{ij}$ and $\phi_{ij}$ are defined as before.

We’re actually overcounting the degrees of freedom here - due to Hemiticity, we have \(H = \sum_{\langle ij \rangle} it_{ij} (e^{i\phi_{ij}} - e^{i\phi_{ij}}) c_i c_j\) That turns into a $\sin \phi$, i.e. the only “phase” it can introduce is $\pi$.

I claim that the Majorana version of the theorem only makes sense when you restrict to the case $\phi_{ij} = \pm \pi/2$.

Theorem statement

Under the conditions (A1), (A2) from before, the optimal flux around a loop $\gamma$ is again $\pi$ if $| \gamma | \sim 0 \ \text{mod} 4$, 0 otherwise.

\textit{Proof attempt}

Again, take an arbitrary loop and cut the Hamiltonian into left, right and middle parts using the site-avoiding mirror:

\[H = \sum_{\langle ij \rangle_L} t_{ij} u_{ij} c_i c_j + \sum_{\langle ij \rangle_R} t_{ij} u_{ij} c_i c_j + \sum_{i \in L, j \in R} 2 t_{ij} u_{ij} c_i c_j\]Now, $u_{ij} = \pm 1 = u_{ji}$ takes the place of the continuusly variable phases from before, and the $t_{ij}$ are constants. It should be obvious now that we can apply the ATR, and recover

$ u_{i,j} = u_{Pi,Pj}$

In terms of signs, that means you get an automatic factor of -1

Concluding remarks

There are a number of important generalisations that are possible that introduce spin indices and additional Hubbard type fermion interactions, but the proof presented here is complete on its own and captures the essence of the result.